Ulysses

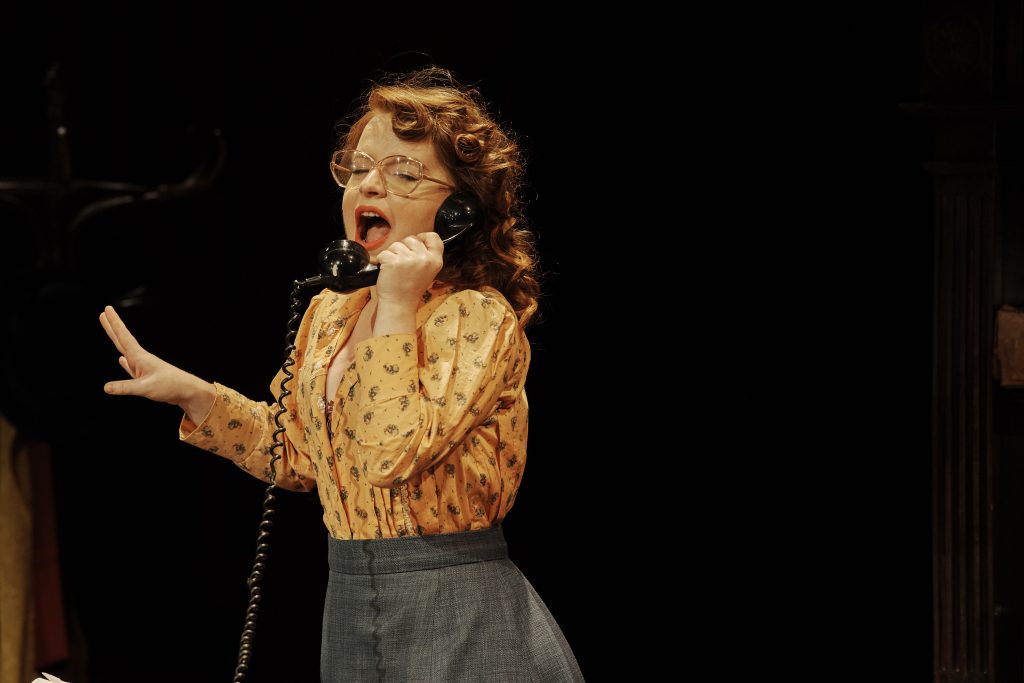

Caitriona Ennis in the Abbey Theatre production of Ulysses

Ulysses

A stage adaptation of James Joyce’s novel by Dermot Bolger

My ideal audience for this adaptation are people who always wanted to read Ulysses but felt daunted. They may be surprised to find that it remains a book about themselves and people they know. Audiences won’t leave knowing everything about Ulysses, no more than I’ll ever comprehend the fullness of Joyce’s vision, no matter how often I read his novel. But I hope they are sufficient engaged by its human dramas – Bloom’s subtle triumphs; Molly’s all too human contradictions and Stephen’s isolation – to once again begin to read this superb chronicle of our capital city: one of the greatest and truest novels of all time, whose author I salute and in front of whom I stand in awe.

Synopsis

Described as ‘Absurd, brilliant and profound’, Dermot Bolger’s adaption of Joyce’s masterpiece is Ulysses as you never imagined it before: a superbly theatrical homage to Joyce’s chronicle of Dublin life and the greatest novel of all time. With his wife Molly waiting in bed for the nefarious Blazes Boylan, Leopold Bloom traverses Dublin, conversing in pubs, graveyards and brothels, enduring ridicule and prejudice as he steadfastly clings to his principles and subtly slays his dragons while drawing ever closer to his fateful encounter with the young Stephen Dedalus. Bawdy, hilarious and affecting, Bolger’s adaptation celebrates Joyce’s genius for depicting everyday life in all its profundity.

The text is sufficiently flexible to be staged in various ways. As directed by Graham McLaren for the Abbey Theatre in productions in 2917 and 2018, Bloom’s odyssey was a pandemonium of live music, puppets and clowning; a production that, in the words of The Arts Review, ‘throws its arms wide open and bids everyone welcome’.

Andy Arnold’s 2012 innovative production of the text for the Tron Theatre in Glasgow went on its own odyssey, eventually touring to China, Writing of it in The Scotsman Joyce McMillan noted that ‘If Bloom is the traveller in the story, Molly is the life-force that he both seeks and runs from, a woman who asserts the power of her desire with a force that remains almost as revolutionary today as it was a century ago. And when this stage version of Ulysses focuses on the rhythm of Joyce’s own poetry, in Bloom’s long walk home with Stephen Dedalus towards the big bed where Molly waits and speaks – then, yes, this is a piece of theatre to remember, as rich and glorious as an old scratched ruby, lying at the bottom of some infinitely cluttered drawer.’

The text of this adaption of Ulysses is published by Oberon in London (https://www.oberonbooks.com/ulysses.html)

Other reviews

Dermot Bolger’s beautifully crafted adaptation (carefully and coherently selected from the fiction) has a palpable love for the sensuousness and abundance of Joyce’s language.

Two things, above all, come over very clearly in this production. One is the extraordinarily encompassing nature of Joyce’s vision of the city-life he re-created in Ulysses: the staging, like the book, teems with variousness, and bristles with the sheer delight which Joyce, like Dickens, took in observing at close quarters the foibles and confabulations of everyday human existence. For both authors, such observations were a constantly renewing, life-enhancing experience, and that feeling emanates glowingly from Tron Theatre’s presentation. The other is the humour of Joyce’s writing. We know it’s there, of course, mischievously stalking its way through virtually every page of the novel. Hearing it aloud, though, is different – the lilt, the droll half-emphasis, the knowing lean upon a particular syllable or consonant. Arnold points these things up tellingly with his actors, who don’t milk the text unduly, but regularly set it loose to work its comic magic. Joyce’s partner Nora regularly complained of being kept awake at night by her husband laughing loudly as he worked on Ulysses, creating the gallery of characters who have since become fictional immortals. Dermot Bolger and Andy Arnold understand that laughter, and give a generous measure of it back to audiences in this funny, touching, provocative, and stimulating production.

Adapter’s Note

Dermot Bolger

If readers feel daunted at the prospect of reading Ulysses, imagine my trepidation at being asked to transpose Joyce’s masterpiece of 265,000 words – in 18 episodes alternating through a dazzling array of linguistic styles – for the stage. Then I realized that my terror as a playwright reflected the apprehension many readers feel when approaching it as a book. My starting point became Nora’s complaint that Joyce kept her awake, laughing while writing it. I quickly realised why Joyce laughed at subtly getting under the skin and prejudices of the claustrophobic Dublin Stephen must flee from. Joyce’s writing teems with brilliant virtuosity, but also with insights into the human condition that remain equally true today.

What impressed me most as a reader scared me as a playwright. Joyce not only created remarkable characters in all their contradictions, but Ulysses expands to encompass an entire city. One difficulty about adapting Ulysses is that it could expand into fifty plays. I needed to focus on two journeys that being together a cuckolded, ridiculed man (who has lost a son but never loses his humanity) and a young man estranged from his own father, intent of true independence by refusing to let any physical, nationalist, religious or moral boundary limit his intellectual freedom. No playwright can match Joyce’s gargantuan vision. I could only hope those elements which fascinated me might intrigue an audience.

An immediate theatrical problem was Molly’s soliloquy – a brilliant one woman show in itself – but in danger of unbalancing any adaptation. However, this gave me a clue towards reimagining the novel as a play. What if I started at the end: with Bloom falling asleep in bed beside Molly? He could be led back through the day’s events in his sleep, by characters who change at the drop of a hat, instantaneously transporting him to different locations inside the illogical logic of a dream. Therefore “real time” is when Bloom sleeps and Molly lies awake, agitated by her torrent of thoughts. This allows her soliloquy to punctuate the play, breaking up (and retrospectively speculating upon) the episodes her sleeping husband relives.

I first read Ulysses as a schoolboy too young to understand Bloom. Reimagining it now I envy his relative youth and remain enamoured by his steadfastness in clinging to his principles amid public ridicule. One by one he slays his dragons in ways so subtle they barely notice his victories. I love his words to Stephen late at night, when they amiably agree to disagree about life. Bloom says: “I resent violence or intolerance in any shape or form. A revolution must come on the due installments plan. All these wretched quarrels, supposed to be about honour and flags. It’s money at the back of everything, greed and jealousy.”

Bloom strikes me as a different type of Irish patriot – even if the drinkers in Barney Kiernan’s pub don’t regard him as truly Irish – because he is a Jew of Hungarian descent. He the sort of patriot who does essential, unglamorous things because a nation is built by the due instalments plan. As a writer I’m proud to share the same city as Joyce. As a citizen I’m proud to share the same city as Bloom – the cuckolded husband, the lecher after shapely ankles, the father carrying bereavement in his heart, the son who understands the silent taboo of suicide, the lowly advertisement agent, regularly sacked because of his opinions, who suffers humiliations but remains steadfast amidst his contradictions.

Details and Rights

The text of this adaption of Ulysses is published by Oberon in London (https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/ulysses)

For rights enquiries please contact http://permissions.curtisbrown.co.uk/