Hide Away: A new novel

Hide Away: A new novel

My thanks to New Island Books who published my fifteenth novel, “Hide Away” in Sept 2024. The publisher’s blurb reads as follows:

“Hidden behind the walls of Grangegorman Mental Hospital in Dublin in 1941, four very different lives collide, all afflicted by wars, betrayals and trauma. Gus, a shrewd attendant, is the keeper of everyone’s secrets, especially his own. Two War of Independence veterans are reunited. One, Jimmy Nolan, has spent twenty years as a psychiatric patient, unable to recover from his involvement in youthful killings. In contrast, Francis Dillon has prospered as a businessman, until rumours of Civil War atrocities cause his collapse, suffering delusions of enemies seek to kill him. An English doctor named Fairfax has fled London after his gay lover’s death. Desperate to rekindle a sense of purpose, Fairfax tries to help Dillon recover by getting him to talk about his past. But a code of silence surrounds that traumatic Civil War. Is Dillon willing to break his silence to find a way back to his family?

In this superb evocation of hidden worlds, Dermot Bolger explores the aftershock within people who participate in violence and the fault-lines in any post-conflict society only held together by collective amnesia.”

Researching the fate of these veterans admitted to the Grangegorman Psychiatric Hospital fed my fascination about that asylum. Now a new university campus, back when the novel is set it was home to 2,000 patients. Established in 1814 as the Richmond Lunatic Asylum, Grangegorman became a porotype for a chain of similar asylums across Ireland. Admission was easily secured. By 1900 one in every two hundred Irish people were incarcerated in an asylum. If being admitted was easy, being released was less so. Families were sometimes so happy to be rid of bothersome relatives, that they never even bothered to claim back the personal possessions stored in the attics there.

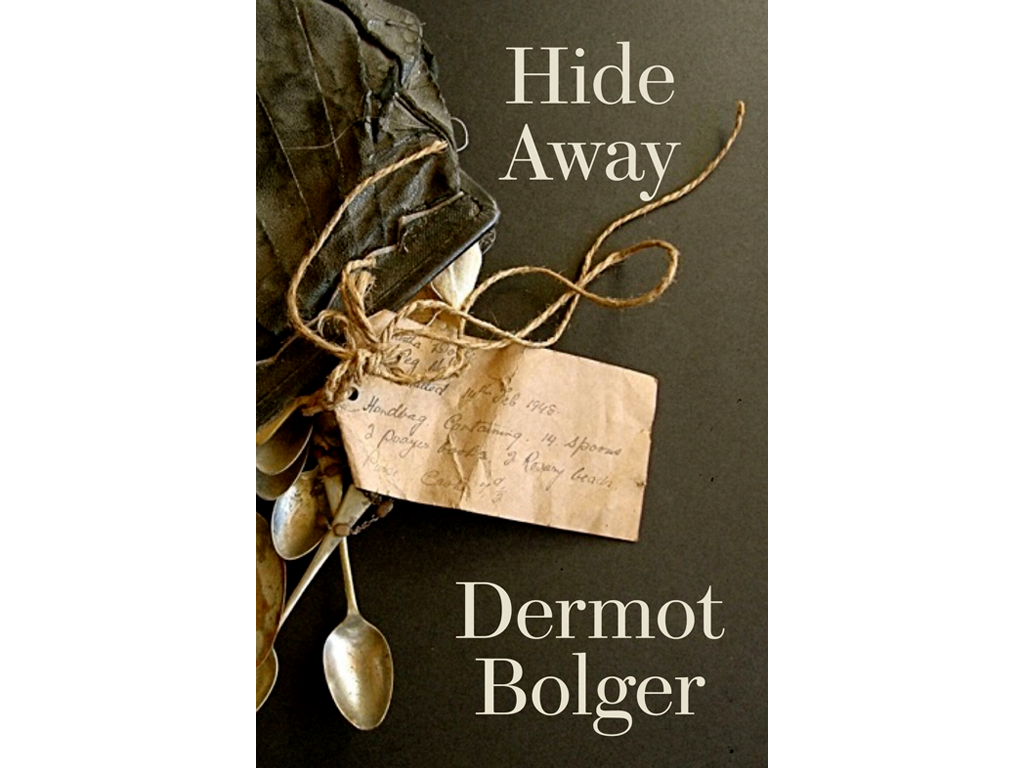

My fascination was fed by viewing a deeply moving 2014 installation by the artist Alan Counihan, entitled “Personal Effects: A History of Possessions”, which focused on those belongings left behind by dead or discharged patients from St. Brendan’s Psychiatric Hospital, Grangegorman. I am honoured and grateful that the artist has allowed me to use on the cover of this novel, a detail from one of his photographs of those forgotten possessions.

Details of the novel can be found on https://www.newisland.ie/

Early Reviews of Hide Away

“In the exquisite Hide Away, Dermot Bolger mines Ireland’s fractured psyche. With superb characters and a haunting ending, this tale of post-Civil War Ireland is a penetrating read. Dermot Bolger’s writing is very well attuned to these closely guarded fault lines that separate Irish people’s private lives and public lives. His new, surefooted novel is set in 1941 amid the mutually agreed-upon code of silence following the Civil War… Bolger has done an exquisite job of coming up with characters that perfectly encapsulate this theme of secrecy; they are the interlocking traumas and commonalities that are apposite of the time. The milieu that causes such guardedness is also expertly handled. Grangegorman itself is like a living embodiment of shunned realities: it’s there so that citizens outside don’t have to take a hard look at themselves… The novel’s haunting ending is really satisfying in how it resists satisfying the reader and avoids a sense of closure that would be wholly unsuited to the doleful reality of the time. It implies the possibility of deliverance through candour while also showing how it’s next to impossible in a society that would rather keep their secrets and transgressions hidden away in the shadows.”

- Rory Kiberd, The Sunday Business Post.

‘Betrayal – of trust, of comradeship, of ideals – is a subsidiary theme of Hide Away, but the novel’s main drift is to underscore the harm done to individuals complicit in violent acts, in slaughter and destruction and executions in the night… It’s a bleak subject, treated here with the sharpest awareness of historical troubles and taboos. Hide Away, against the odds, makes an invigorating read, for all its encapsulation of a broken world.’

– Patricia Craig – Irish Times

“Hide Away is an astute character study concerned with guilt, betrayal (personal and public), and the secret lives of those we love.

“People only want to hear about good wars with bold deeds to sing of. You and I had bad wars. Bad wars are best kept quiet. I serve my country by staying put behind these walls where no one need witness the aftershock.”

Jimmy Nolan speaks these words in Dermot Bolger’s Hide Away. The novel is set in Grangegorman Mental Hospital, where Nolan has spent almost 20 years as a psychiatric patient because of his involvement in a brutal killing.

The “aftershock” he refers to is the book’s cornerstone and has two essential aspects. The first is the personal repercussions, that went largely unspoken, for the combatants who inflicted violence during the War of Independence and Civil War. The second is the fledgling country’s public trauma, suppressed by sacrificing a tangled, complicated history for a simplistic, sanitised narrative.

“War is easy,” a character suggests. “It’s peace that’s hard work.”

In 1977, Bolger, an 18-year-old factory worker, founded Raven Arts Press, which published early works by Patrick McCabe, Colm Tóibín, and Sebastian Barry.

Initially a poet, the Finglas native has written more than 20 plays. Hide Away is franked with flourishes from the author’s experience across genres. The poet’s precision of language is evident throughout: The way Fairfax found “sanctuary” in Charles prefigures the doctor’s arrival in Grangegorman. The prominence of nimble, convincing dialogue attests to Bolger’s skill as a playwright.

Locating the action almost exclusively within the walls of Grangegorman conjures an appropriately oppressive atmosphere, but this is often leavened by Bolger’s trademark wry humour. “Generally,” suggests an attendant, explaining the Irish to Fairfax, “we say everything that needs to be said by saying nothing.”

- Brendan Daly, Irish Examiner

“Hide Away is as good as anything the multi-faceted writer has given us thus far. It begins with a night-boat crossing to Dublin in 1941. The “lights glittering in the distance” look unnatural to the English doctor, Fairfax, after two years of enforced blackouts in England. Cardboard had to be placed over the headlights of the car that spirited him away, with only the barest pinpricks of light visible. Hard-to-obtain work and travel documents had been procured in establishments “where gentlemen could enjoy the company of fellow gentlemen in the billiards room” and in more secretive clubs where men enjoyed each other’s company “in a more surreptitious manner”.

Fairfax had partitioned his life, but all he really cared about “was that sanctum in Putney which he shared with his lover Charles”, the same Charles who welcomed the blackouts for turning “all of London into a version of Hampstead Heath, brimming with sexual possibilities”. Charles’ exploitation of these opportunities is the reason Fairfax’s life was blown apart when a bomb hit a side street and his lover’s body was found entwined with another.

He isn’t under any impression that he is escaping to some kind of safe harbour. He’s heading to Dublin to take up a low-paying position in the Grangegorman psychiatric hospital, a place that Charles, who had spent army years in Ireland, referred to as a “hellhole”. Fairfax would be “too soft to ever work” in, he told his lover. Overwhelmed by grief, part of Fairfax wants to prove Charles wrong and part of him needs a place where nobody knows him.

Bolger’s masterful novel pokes at the many sores that festoon a country “barely held together by the invisible sticking plaster of everyone keeping their secrets”: the treatment of homosexuals, the use of the health system as a dumping ground for relatives who were in the way and the burying of historical scars behind hospital walls. That he manages to address this in a layered work that’s deeply affecting and, on occasion, delivers a side-line in the kind of Dublinese that Flann O’Brien would have considered a good day’s work is testament to his powers as a writer.”

- Pat Carty – Irish Independent

“From a psychiatric patient haunted by past violence to a businessman unravelling under the weight of old atrocities, Bolger explores the silent scars of Ireland’s post-conflict society. With vivid storytelling, Hide Away offers a profound look at the human cost of violence and the unspoken struggles that linger long after the fighting ends.”

– Claire Lindsay, The Impartial Reporter