I am delighted that this new play is running in the Civic as part of the Dublin Theatre Festival from Oct 1st to Oct 12th 2024 and then transferring for two weeks to the Viking Theatre in Clontarf. People might be interested to discover how a madcap scheme to somehow find the money to see Ireland play Denmark in Copenhagen forty years ago, when I was an impoverished poetry publisher working over a bookie’s shop in Finglas, led not just to this play but to two previous plays about the same characters who have lived in my imagination, ageing at the same rate as me, since 1990. The article below, from The Sunday Independent, tells that story.

Home, Boys, Home: A Forty Year Odyssey

Dermot Bolger

Forty years ago in 1984, I was as impoverished as anyone would be who ran a tiny poetry press from an office shared with a plumber above a Finglas bookie’s shop. Our phone line was linked to the bookie’s electronic feed so that my phone calls, hoping to obtain Arts Council funding or persuade foreign publishers to co-publish Irish writers, were constantly interrupted by announcements like “Winner all right in the 2.45, Kempton”.

Disgruntled punters in that bookies dreamt of pulling off audacious betting coups. But none could be as audacious as the scheme that Jorge (my faithful underpaid assistant) and I concocted, as we sat on unsold stacks of books that were the only furniture we possessed.

Eoin Hand – an honourable man disgracefully undermined by FAI – was Ireland’s soccer manager. His successor, Jack Charlton, later led us to unimaginable successes. But forty years ago Jorge and I didn’t dream of attending World Cup finals. Our dream was to find enough money to see Ireland play Denmark in a forthcoming World Cup qualifier in Copenhagen.

Our improbable plan was to persuade a bank to sponsor a scheme we invented called Raven Arts Poetry in School. To our amazement, a thoroughly decent man, the great rugby player Willie John McBride, working for Northern Bank, agreed to give us £1,000. Jorge cycled to every school in Dublin to deliver a set of free Raven books. After expenses, we had just enough money left for match tickets, flights to Copenhagen and two sleeping bags in hopes of finding a floor to crash on.

All seemed well until a journalist phoned a conservative headmaster who had not seen the books but still felt able to condemn them, and especially one poet who today is a beloved mainstay on the Leaving Certificate. Jorge and I returned from playing pitch and putt to learn from the plumber that our phone hadn’t stopped ringing. Unable to contact us, the journalist quizzed the unfortunate Willie John McBride. The headline next day read: “Bank Poems fit for Toilet Wall Says Angry Head”.

The VEC banned our books but we made it to Copenhagen. It was the most eye-opening Ireland match I’ve ever attended. Not for the game itself – Denmark slaughtered us three nil – but for the hard core pre “Jack’s Army” Irish fans I met when seeking a floor to sleep on. Some had travelled from Ireland. But many were children or grandchildren of Irish emigrants to Britain. Their presence among us mirrored the composition of our team. British-born players like Barnsley’s Mick McCarthy and Rotherham’s Jim McDonagh (who responded to a phone call asking him to declare for Ireland by reciting the 1916 Proclamation) seemed to represent our relations forced to emigrate.

My father was from a Wexford family of seven, my mother from a Monaghan family of eleven. Almost all emigrated. Most of my cousins have Leicester and Luton accents. I only possess a Dublin accent because my father was a sailor, sending money home. 80% of Irish-born children in the 1930s were forced to leave, to the relief of governments who used emigration as a safety valve on social unrest, sluicing away the disaffected, while Ministers for Finance gleefully factored emigrants’ remittances – all the ten shilling notes sent home – as an invisible export, keeping the economy afloat.

Often in England they faced similar prejudices that new arrivals in Ireland often face. One newspaper series of interviews with Irish nurses in Britain in 1951 was entitled, “They Treat Us Like Dirt.” But as Joseph O’Connor noted, “At the heart of the Irish emigrant experience there is a caution, a refusal to speak,” which meant that the Irish emigrant experience was rarely represented in literature.

A third set of Irish supporters in Copenhagen made an equal impression of me. Three lads with Kerry accents told me they’d arrived by bus. “From Tralee?” I asked and they laughed. “From Cologne. Every Irishman in the factory is here.” These were my generation, forced to emigrate to seek work at a time when Brian Lenihan Senior smugly told Newsweek magazine, “We can’t all live on the one island”.

In 1988, when Charlton brought footballing success, I stood on a terrace in Gelsenkirchen to watch Ireland agonisingly lose out on a semi-final place at Euro 88, thanks to an offside Dutch goal. By then the ranks of Irish fans were swelling, but the London Irish and the new Cologne and Eindhoven Irish remained.

In 1990 Michael Colgan asked me to write a play about soccer for the Gate Theatre for the Dublin Theatre Festival. I set it at that Dutch match in Euro 88, where eleven Irishmen – two black, eight born abroad – passionately represented all strands of Irishness. The play was about three young Dubliners – Eoin, Shane and Mick – who’d spent years scavenging money to follow the Irish team, hoping to one day witness a moment of glory and come home like heroes, with stories to tell.

That glory comes when Ireland beat England. But they have no one to tell because, after the tournament ends and they go their separate ways, none are returning to Ireland. They are economic migrants: Eoin, living in Hamburg; Shane, working for Philips in Eindhoven and Mick about to disappear as an illegal emigrant to New York. They suddenly feel like they no longer belong to the Ireland they left or the new countries they live in. But in the menagerie of accents supporting that Irish team, they find a version of Ireland broad enough to encompass their uncles and aunts forced to emigrate and their own future children who would grow up abroad with Irish cheekbones and foreign accents, bewildered by their father’s lives.

The play was called “In High Germany”. It starred Stephen Brennan in the Gate, Liam Cunningham in RTE’s televised version and Ray Yeates in its New York premiere. But numerous emigrating Irish actors took it in their back pocket, feeling that it represented something of their lives as they staged it cities as diverse as Tokyo and Helsinki. One Irish actor in Romania electrocuted himself by touching a live wire on stage and woke up to find the audience intensely watching, presuming this was part of the play.

The academic, Dr Kevin O’Sullivan, noted how, by exploring Ireland’s history of emigration and immigration through the backgrounds in Ireland’s soccer teams, In High Germany “raised big questions about race and what it means to be Irish.”

But the three characters in the play refused to leave my imagination alone. Patrick Kavanagh once noted Marcus Aurelius’ observation that, while he aged, people on the street remained the same age – twenty-three on average. In contrast, Shane and Mick and Eoin aged at the same pace as me in my mind, refusing to go away.

By 2010, I was no longer the young man who wrote about them in 1990, but they weren’t young either. I returned to them in a second play, “The Parting Glass”, which toured Ireland, America and Britain. This focused on their lives between 1988 and being reunited in Paris in 2009, where Thierry Henrys cheating hand robbed Ireland of a place in another World Cup finals.

In “The Parting Glass” Eoin tries to return to Ireland to care for an ageing parent. During the collapse of Celtic Tiger, he loses everything, including his German born wife, unexpected killed in a car crash. When writing the play, I tried to imagine his unimaginable grief at such a loss. Then, tragically days before the play opened, I lost my own wife, who collapsed when swimming with our son. Every emotion I invented for Eoin felt like a prophecy, as I found myself forced to live out his same journey of grief.

But Shane and Mick and Eoin were still not done with me. As I turned 65 this year, I asked myself what those carefree friends, who stood together at Euro 88, would make of this new multicultural Ireland if they returned now, perhaps feeling more in common with new arrivals from foreign countries than with their contemporaries who stayed.

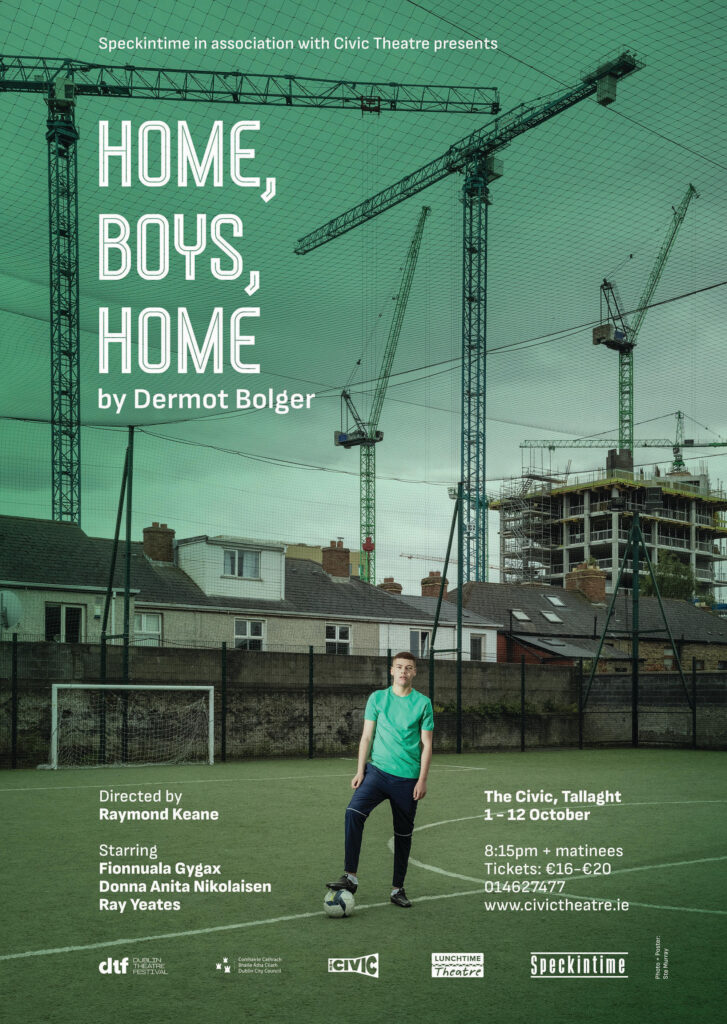

Leaving a country is never easy. Returning after forty years is even harder. 34 years after I created these characters for the 1990 Dublin Theatre Festival – I am now bringing their stories to a conclusion in the 2024 Dublin Theatre Festival, with a new play, “Home, Boys, Home,” at the Civic Theatre from Oct 1st to 12th

Shane was always the cynical joker, humour being his weapon of defence in his life in Holland. But now he drops his wise-cracking mask when returning to a multicultural Ireland where he feels disconnected. Then he discovers surprising links: an unknown daughter, a black teenage grandson trying to define his identity and gangland figures threatening the boy’s future. Can he protect a grandson who is unaware of his existence and can they both find ways to feel they truly belong in Ireland today?

Hopefully, ten years from now, the faces in Dáil Éireann will look as diverse as the faces on our streets, although I’ll not hold my breath. But as Shane tries to adjust to being home, the composition of Ireland’s football team remains for him the true barometer of Ireland’s changing identity. It represents a shared sense of belonging, whether you are from Cabra like Shane, or your father is from Nigeria like Gavin Bazunu or, like Chiedoze Ogbene, you chose to wear an Irish jersey despite having being born in Africa.

“Home, Boys, Home” is a standalone, independent play. I don’t know if you’re a younger theatregoer, entering the Civic Theatre, in the Tallaght suburb that produced sporting legends like Richard Dunne and Rhasidat Adeleke, or if you previously encountered these three phantoms of my imagination. I just hope that you enjoy the end of an imaginative journey that began one afternoon above a Finglas bookies when two penniless young men concocted a plan to find enough money to stand on a terrace in Copenhagen, cheering on eleven players who gave their all for Ireland