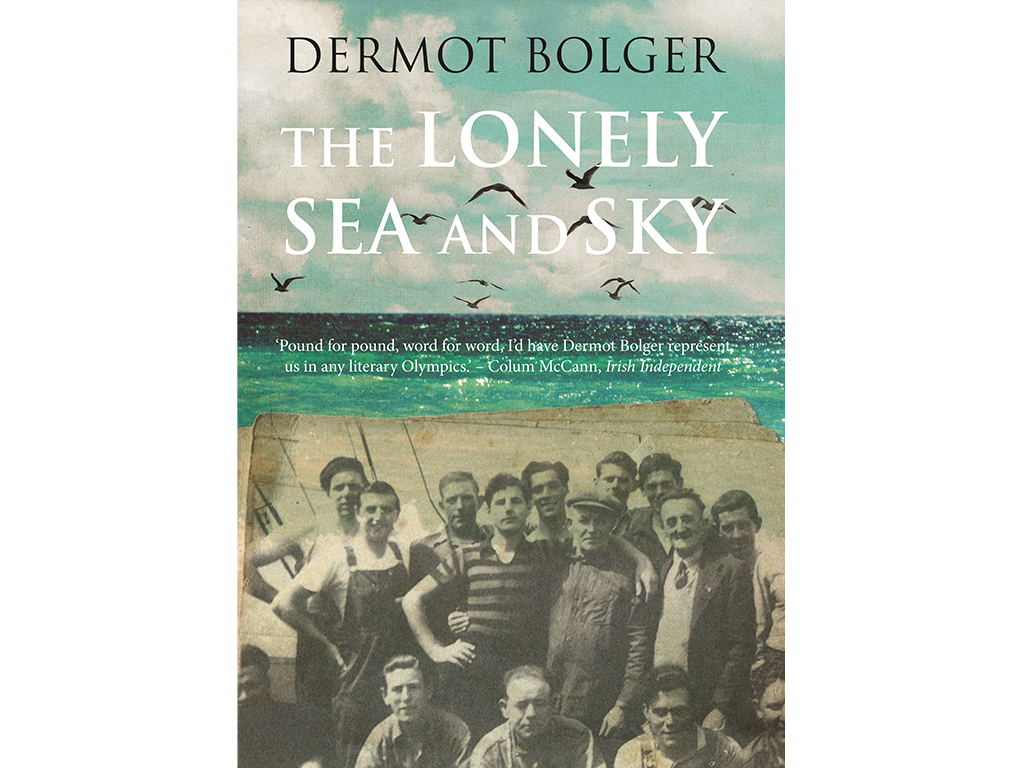

The Lonely Sea and Sky

The Lonely Sea and Sky

Publisher’s synopsis

Myles Foley gripped my soaked jumper. ‘Before his ship sank he was a Nazi: now he’s a drowning sailor. Out here, we’re all sailors. Your father and grandfather understood that. Are you going to disgrace their memory?’

Part historical fiction, part extraordinary coming-of-age tale, The Lonely Sea and Sky charts the maiden voyage of fourteen-year-old Jack Roche aboard a tiny Wexford ship, the Kerlogue, on a treacherous wartime journey to Portugal.

After his father’s ship is sunk on this same route, Jack must go to sea to support his family – swapping Wexford’s small streets for Lisbon’s vibrant boulevards: where every foreigner seems to be a refugee or a spy, and where he falls under the spell of Kateřina, a Czech girl surviving on her wits.

Bolger’s new novel is based on a real-life rescue in 1943, when the Kerlogue’s crew risked their lives to save 168 drowning German sailors – members of the navy that had killed Jack’s father. Forced to choose who to save and who to leave behind, the Kerlogue grows so dangerously overloaded that no one knows if they will survive amid the massive Biscay waves.

A brilliant portrayal of those unarmed Irish ships that sailed alone through hazardous waters; of young romance and a boy encountering a world where every experience is intense and dangerous, this is Bolger’s most spellbinding novel, and the work of a master storyteller who is one of Ireland’s best-known novelists, playwrights and poets.

Publication Details and Rights

The Lonely Sea and Sky is published in paperback and on kindle by New Island. All rights enquiries should be directed to Edwin Higel, Publisher, edwin.higel@newisland.ie, or Mariel Deegan, General Manager, mariel.deegan@newisland.ie

To purchase a copy click here http://newisland.ie/product/the-lonely-sea-and-sky/

Reviews

It is a full-bodied barnstormer, a coming-of-age tale of wanderlust ideal for readers aged 12 to 92. It is an ocean-going epic of sacrifice and derring-do against the backdrop of war-torn Europe. It is a paean to a fledgeling Ireland trying to find its feet as the ground moves beneath it. It is all these things and yet it releases submerged thematic buoys to the surface in that effortless Bolger manner. You can only do this if your craft has been carved to precision by time.

Bolger’s rendering of the transformation of ordinary men, who have chosen a risky way of life, into truly heroic figures makes for engaging reading.

Bolger’s unforced style sings with colour, humour and excitement. But it’s the way he smuggles “the bigger themes” into the narrative hull that grants this historical fiction “modern classic” status.

Bolger creates a personal, heartrending and atmospheric tale of the lives of these Irish sailors during a period of great international conflict… Dermot Bolger has done them justice in producing such a finely crafted and extremely readable tale which brings their story to life.

That mother of life, that coffin of death, the ocean will continue to compel writers to their task. The Lonely Sea and Sky is a beautiful novel that will suit all ages.

Author’s Note

Dermot Bolger

Looking back, I realise I should have asked my father more about his wartime experience on tiny Irish ships undertaking dangerous voyages to Lisbon. But he was reluctant to discuss those occasions when his ship was bombed. Like many of his generation, there were memories he didn’t wish to articulate aloud.

He hated fuss. Ireland had desperately needed seamen to risk their lives to import vital supplies to keep its economy just about functioning. But my father maintained that it was only a job. His crewmates were ordinary seafarers: no heroics or histrionics. Just banter and companionship and small-scale smuggling to earn a few extra bob because the shipping companies would stop whatever wages their families were due from the minute that a torpedo shattered their ship or the Luftwaffe dropped bombs on Irishmen, bereft of uniforms or weapons, huddled in wheelhouses. If you clambered into a lifeboat or drowned at sea, you did so on your own time.

The Edenvale

My father died in 2011, leaving behind a biscuit tin of Discharge Books which captains had stamped VG (Very Good) every time he signed off a ship during forty-four years as a ship’s cook. His career started at sixteen when a neighbour got him his first job at sea. His life at sea saw him being on a small Welsh ship at Scapa Flow in 1939 when the Royal Oak was torpedoed at anchor: 833 lives lost in the conflagration. It saw him jump from a sinking vessel, The Cameo, taking with him only a ragdoll in his pocket for his daughter. It saw spend much of the war on the MV Edenvale, being bombed several times on route to Lisbon.

My father rarely mentioned those times, but once recalled huddling with crewmates in the Edenvale’s wheelhouse when a bomb smashed through the funnel and rolled across deck into the sea, miraculously unexploded, while the Luftwaffe pilot returned to machine-gun the deck. Like its sister ship, the equally tiny MV Kerlogue, the Edenvale weren’t built for long voyages. But when World War Two started, Ireland had just 56 small ships. This “Lilliputian fleet” became Ireland’s link to the outside world, especially to American supplies landed in neutral Lisbon.

While Allied ships sailed in blacked-out convoys, Irish ships sailed alone and lit up, hoping that U-boats would respect their neutral markings. But instead Irish ships were attacked on 41 occasions, with 149 crewmen killed and 38 wounded. During that same time this tiny makeshift fleet saved 521 lives, rescuing British, German, Dutch and American survivors.

After my father’s death I thought a lot about those unarmed Irish sailors being used pawns in a chess game between de Valera and Churchill. De Valera used these ships as his unarmed front line; displaying Ireland’s neutrality – and therefore its de facto independence, prior to a proper declaration as a Republic in 1949 – by sailing lit up, protected only a tricolour pained across their deck.

I doubt if my father read many of my novels. But I wanted to honour his memory – and the men he sailed with – by writing one seagoing book, The Lonely Sea and Sky, that might hopefully contain the old fashioned storytelling he enjoyed reading in his cabin at night.

Homage to his Generation

Although elements of his life are woven in, the novel is a homage to the real-life crew of the Edenvale’s sister ship – the Wexford Steamship Company’s M V Kerlogue – who were involved in an astonishing sea rescue.

The Lonely Sea and Sky describes how a young Wexford boy lies about his age to embark on his maiden voyage on the tiny Kerlogue in December 1943. His has to become the wage-earner after his father’s ship is sunk on this same Lisbon route. He swaps Wexford’s small streets of Wexford for war-time Lisbon, crammed with refugees and spies.

December 29th, 1943 dawned like an ordinary day to the Kerlogue’s ten-man crew returning from Lisbon. But by nightfall 168 shipwrecked German sailors would crammed every inch of their dangerously overloaded ship. The crew had been attacked previously and feared the worst that morning when a German plane circled them. But no bombs came. Instead, the pilot signalled SOS. Altering course, they encountered a sea littered with bodies. The Chief Officer noted: “As rafts rose into view on the crest of giant waves, we could see men on them and others clinging to the sides. At first, we did not know if they were Allied or Axis until someone noticed long ribbons trailing downwards from behind a seaman’s cap which denoted they were German Navy men.”

Working under floodlights, the crew spent ten hours rescuing every man they could pack on board. A senior German officer asked the Kerlogue to land his men in France. As a neutral ship, the Kerlogue’s captain (who had survived being sunk by the Nazis some months previously) refused. Although the Germans could have overpowered his crew, they accepted his decision.

14 Germans jammed the wheelhouse, blocking the view of the Irish sailor trying to steer. The engine room was so packed that the Chief Engineer couldn’t reach machinery and needed to signal to survivors to turn instruments. Four badly injured Germans died on board. Others had to be left to drown, when no space on the dangerously overloaded ship, whose deck was barely above the waves.

The British authorities requested that ship dock in Wales, where the survivors would become prisoners of war. But, just as he refused to bow to German demands to land in France, the Irish captain ignored these instructions and maintained his neutrality. He nursed his packed ship to Cobh, with the Germans interned in the Curragh Camp until the war ended.

The Kerlogue’s crew obeyed an unwritten code to save any lives they could. In risking their lives, they recognised the drowning Germans not are combatants, but as fellow sailors and honoured what sailors traditionally believe the initials SOS stand for: “Save our Souls”.

Two months later the German Navy repaid the compliment by killing another eleven unarmed Irishmen on the Arklow schooner Cymric on this Lisbon route. Among them was the neighbour who first took my father to sea.

My fictional Kerlogue crew are phantoms of my imagination. I don’t presume to speak for the real crew involved in that rescue or the crew on any ship. I can only salute them and hope that I’ve paid some small tribute to their courage in a novel that my father might hopefully have enjoyed reading during one of his life’s many voyages.