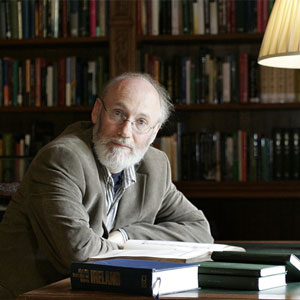

Dermot Bolger is one of modern Irish literature’s most respected writers, best known for his unmistakable voice as a Dubliner. The River Liffey practically courses through his veins, and some of his peers would be inclined to agree. Joseph O’Connor has said of Dermot’s work, “Bolger is to contemporary Dublin what Dickens was to Victorian London.”

With ten collections of poetry, fourteen novels and sixteen plays to his name, to say Dermot is industrious is probably a gross understatement. Not only has he created an outstanding body of work as an individual, he set up Raven Arts Press in 1977 at eighteen, co-founded New Island Books in 1992, conceived the bestselling collaborative novels Finbar’s Hotel (1997, Picador/New Island) and Ladies’ Night at Finbar’s Hotel (1999, same). He has edited many anthologies, including The Picador Book of Contemporary Irish Fiction,and has been a Writer Fellow at Trinity College Dublin. Some of his novels include The Journey Home (1990, Penguin), Father’s Music (1997, HarperCollins), Tanglewood (2015, New Island), and The Lonely Sea and Sky (2016, New Island). His debut play, The Lament for Arthur Cleary (1989), won the Samuel Beckett Award. His other dramatic works include The Ballymun Trilogy (2010), which depicts forty years in a Dublin working class suburb and more recently, his monumental expanded adaptation of Ulysses, staged by the Abbey Theatre in 2017.

Dermot’s new novel, An Ark of Light, follows Eva Fitzgerald; a central character from The Family on Paradise Pier (2005). The journey begins in 1949 when at age forty-six, Eva takes the bold step of leaving her husband Freddie in Co Mayo. Over the years she is transported to Dublin, Spain, the Isle of Wight, the Kenyan Serengeti, London, and later to her Ark caravan in a Mayo field. Based on the life of his long-time friend Sheila Fitzgerald, the inspirational narrative brings us an extraordinary, uncompromising woman far ahead of her time. Throughout the substantial volume are stirring themes of familial bonds and social politics in a new world. We could all take a leaf out of Eva’s book, spurred on by the words of her mother on her wedding day; “There is one thing you must never lose sight of. No matter what life deals you, promise me that you will strive tooth and nail for the right to be happy.”

Dermot Bolger lives in Drumcondra, Dublin. He is currently working on his next play.

An Ark of Light (€14.95) is published by New Island and available from bookshops nationwide.

On home

I was born in Finglas, lived for a time in Glasnevin and then thirty years ago purchased the small house in Drumcondra where I now live. Looking at a map I noticed that I was moving inexorably towards the sea, but now I realise that, with global warming, the sea is probably inexorably moving towards me so I have stopped here. Drumcondra has changed greatly in three decades but I have many of the same neighbours and love its closeness to everything, being a twenty-five minute walk to town and full of new cafés and restaurants. Although for me of course Drumcondra’s true renaissance will only be complete when Shelbourne regain their rightful place in the top tier of Irish soccer and launch another Don Quixotesque assault on the lower slopes of the Champions League.

On childhood

I grew up in Finglas Park in Finglas and indeed was born at home in the back bedroom there in 1959. I found it a fascinating place for a writer to grow up in because there was just a juxtaposition of people of different backgrounds. Almost all my neighbours were people like my parents who had come up to Dublin from the country and brought their country habits with them, so the back gardens of my street were rural in many ways with long rows of potato beds and hens being kept, whereas the more modern estates were populated by people who had moved out from the inner city. Therefore you saw a great glimpse into two different backgrounds co-existing side by side with the children of each creating their own new culture from it, be it in the poems of Paula Meehan, Michael O’Loughlin or Rachel Hegarty or the songs of Christy Dignam or dozens of bands creating their own voice in a new space.

On unlimited imagination

I think we are products of our background and environments, but that does not mean that our imaginations or horizons need to be corralled by those backgrounds and environments, although I like to think that I have brought a Finglas perspective – a refusal to be unduly swayed or impressed – to the various worlds I have written about. Certain chapters of An Ark of Light are set on a coffee plantation in Kenya just after Kenyan independence, in a remote Pyrenean village in the late 1950s still under the jackboot of Franco, in the Gay underworld of 1960s London and on Lundy Island in 1970 – worlds about which I have no direct experience, but can hopefully still make as real as any Dublin street. I know that when we started Raven Arts Press in 1979 the Arts Council was initially determined that we stick to community arts, which was a sort of way of putting us in a box, however while we published a new generation of Dublin writers we also published books by major European figures like Paul Celan and Pier Paolo Pasolini, because we refused to have any limit set on our imaginations, while we always remained informed by our formative experiences.

On creating

I have been lucky enough to write my novels in some unlikely places. Two were written in the watch room of the Baily Lighthouse. Passengers flying into Dublin may have thought that the light flashing on and off at Howth Head was to warn shipping, but frequently it was just me trying to find the right light switch on my way out. However you don’t always need an isolated room or a full day of doing nothing else to write. Writers work in short bursts. If embarking on a book or memoir, what you need is to take your ambition seriously and insist that others close to you respect those rules. You need to partition off part of each day for yourself – even just one hour when you lock yourself away, when people know you are not to be disturbed, be it in your kitchen or bedroom, when you insist on being allowed the mental space to sit back and see who turns up in your imagination. I currently write in the front room of my house.

On bookshops

Thirty years ago I got married to my late wife with a party in the Winding Stair Bookshop, back when it was an oasis of civility and kinship under the ownership of its original founder, the great Kevin Connolly. The building holds so many special memories that I have never set foot in it since he sold it. I greatly admire The Gutter Bookshop; the extraordinary Kenny family in Galway who have been great supporters of Irish writing going back to very difficult decades; Charlie Byrne’s in that same city; Antonia’s Bookshop in Trim, The Crannóg Bookshop, Cavan and many, many other new arrivals, while it is lovely to see shops that I dealt with in my days as a publisher, like The Waterford Book Centre, Dubray and O’Mahony’s in Limerick, still thriving.

On his “To Be Read” pile

I have Conor Brady’s thriller, The Dark River, by my bed because it brilliantly evokes Victorian Dublin with its political intrigues and I love how he so deftly straddles both the historical fiction and thriller genres. I also have an advance proof of a new novel, Her Kind, by Niamh Boyce, whose debut, The Herbalist, was so impressive, while I am enjoying dipping into the stories and superb photos of Dun Laoghaire pier, in People on the Pier by Marian Therese Keyes and Betty Stenson, which is beautifully produced and the perfect stocking filler for anyone for whom the pier has been part of their lives.

On escape

I generally escape from stress by playing golf, on the premise that no stranger has ever stepped from a bunker and handed me a manuscript, seeking my opinion. On day trips I do love to call into the Wicklow Heather in Laragh for a meal after a day in the mountains. Abroad I love to wander through the streets of Lisbon, a port that my father sailed into on dangerous voyages on small unarmed Irish ships during the war and where my wartime novel about those ships, The Lonely Sea and Sky, is partly set. Lisbon is a city that everyone should explore.

On retreats

I am cautious enough about using writer’s retreats, preferring to simply go to a hotel or somewhere more private if I need to finish something. But I did recently break this habit by spending a month in a truly extraordinary 15th-century castle on a remote hillside in Umbria, called Civitella Ranieri which is run by the Civitella Ranieri Foundation in New York as an artist residency program that invites nominated Fellows and Director’s guests to stay in this castle for a period of between four and six weeks. It is not something you apply for in that you need to be nominated for a Civitella Fellowship. As almost no Irish writers or artists have been there, I have no idea who nominated me or what country they were from, but I found it a truly remarkable experience to work on a new play there.

On Sheila Fitzgerald

If you dream of being a writer you need one person to take you seriously. Our friendship started forty-one years ago in 1977 when Sheila read something about me and sent me an encouraging postcard, saying that, if ever in Mayo, I was welcome to sleep in her caravan and use a nearby wood as a sanctuary in which to write poems. I was eighteen and she was seventy-three but perhaps because I lost my mother and Sheila had lost a son, we felt an affinity. Sheila opened my eyes to new ways of seeing things. Although penniless, she was the richest person I knew because she wanted nothing. She had her beloved dog, Johnny, her books and the cats who shared her caravan along with numerous callers of all ages, inspired by her positivity. Unemployed in Dublin, I’d hitch-hike to sit in her candle-lit caravan, and read her my latest poems. We always talked long into the night and she was unafraid to address her tragedies. Therefore the stories about her in An Ark of Lightwere stories I heard on my first visit to her Ark.

Sheila often talked about writing a memoir and indeed her 1968 passport listed occupation as “writer.” But by 1992, when Sheila was eighty-nine and living in a field in Wexford it seemed unlikely she would write her memoirs. We discussed the idea of my writing a novel about her life. For several nights we sat up in her caravan, making recordings about her life. A year after her death I found those tapes. They let me reconnect with Sheila when she was still in good health and see the totality of her life. I needed to write as a novelist and not a biographer, guided by a line by Sheila on the tapes about how she admired artists with the courage to shape reality into something new. The book explores how Sheila found the courage to leave an unhappy marriage and start on a quest both physical and spiritual: to strip away the veneer of complexity and strive – despite setbacks – to grasp the joy at the core of life. I hope I have captured something of her uniqueness, of her resilience in facing tragedy and her essence of joy.

On Ulysses

I was initially terrified at the prospect of being asked to transpose Joyce’s masterpiece of 265,000 words – in eighteen episodes alternating through a dazzling array of linguistic styles – for the stage. Then I realised that my terror as a playwright reflected the apprehension many readers feel when approaching it as a book. Nobody can call Ulyssesan easy read. Joyce joked about keeping critics busy for centuries. Many critical studies laudably try to open up the book, but some abstruse criticism places barriers around Ulysses being simply enjoyed as a novel. Therefore my starting point was Nora’s complaint that Joyce kept her awake, laughing while writing it. I quickly realised why Joyce laughed at subtly getting under the skin and prejudices of the claustrophobic Dublin Stephen must flee. Joyce’s writing teems with brilliant virtuosity, but also with insights into the human condition that remain equally true today. I loved watching people leave the Abbey talking about the characters as if they were neighbours they had known all their lives.

On what’s next

Strong coffee.